|

Publisher's Forum Issue: 37-4 |

|

Sesquicentennial inspiration Historians

have deliberated about the National Park Service's efforts to restore some

battlefields to their wartime appearance. Battles about accuracy have been refought with the discovery of

additional bits and pieces of newly discovered information. Heritage defenders have marched in defense

of the integrity of century-old museum charters. Reenactors have debated which flags should be

carried at which battle. Collectors

have held vigils praying for a restoration of relic prices to Centennial-era

evaluations.

Kidding

on that last aside, one of the most common topics of contention is what might

have happened had the South been victorious. Speculation about that began the day after Lee surrendered and continues

to this day.

In

1960, Pulitzer Prize-winning author MacKinlay Kantor wrote "If the South Had

Won the Civil War,” which was printed in Look magazine and published in book

form the following year. Kantor's keen

insight brought the political and social issues together in a compelling tale

of "What if?" Having served in World War

II as a news correspondent who witnessed the horrors of war and concentration

camps, Kantor was able to see beyond the simplicities of surface facts. His prize-winning fictional account of

Andersonville, inspired by his wartime observations, brought him international

acclaim. He brought those same powers of

observation and perception into play in his tale of Southern victory in the War

Between the States.

When

I was a youngster during the Centennial, much of Kantor's vision eluded me, but

given the sense of nationalism that pervaded in the Centennial era, I recall being

somewhat conflicted about his conclusion about a peaceful postwar

disunion. I just couldn't imagine the

North and the South being two separate nations. As one nation, we had saved the world---twice. We were united by a new highway system that

made nationwide travel accessible and appealing. Television was making us all laugh and cry

and applaud the same things from Maine to southern California. We were about to conquer space. America ruled the universe and everyone knew

it.

Fifty

years later I find myself utterly amazed that the cohesiveness and national

pride of that era is gone. A half

century of assaults, both within and without, by those seeking a bigger slice

of the pie for themselves or someone they believed deserved it has brought us

to our knees.

Unlike

the schism of 1860, today's isn't a geographic separation but wholly

ideological ones. America today seems as

divided as it was in 1860---or worse. At

least in 1860, Americans were united by a common sense of national pride, an

adherence to traditional values, and a common moral compass. We were separated primarily by politics and

the economies of different geographic areas. Today, it seems we have less in common than we did 150 years ago. Sure, we're still separated by politics and economics,

but were are also splintered into scores of factions of self-descriptions and

self-interest: poor, rich, young, old, gay, straight, pretty, ugly, smart,

stupid, fat, anorexic, believers in God, athiests, and those who simply hate

everyone.

One

would think that commemorating the 150th anniversary of the war might finally

cement the once divided America. It

might give us cause to pause and dwell on all that unites us. With a black president, a man whose

dedication to unity for the world garnered him the world's highest award for

being a force for peace among men, we should by now have made inroads in that

direction. Instead, it seems we have

allowed ourselves to be led in the opposite direction. We have disunity, suspicion of government,

fear, and, yes, racism.

In this atmosphere, I find myself earnestly

wondering: Would we have been better off if Kantor's whimsical vision were

true?

But

that is fiction. Given that the current

state of affairs is reality, we must ask ourselves: What can we do about

it? We don't have the options of 1861

available to settle our differences. We

must seek another solution. We must examine anew what unites us as a people and

as a nation. The only hope we have for

drawing back from the abyss of a gloomy future is to take responsibility for

improving our own plight and those of our families, our neighbors, our

communities, our state, and our nation.

I

know that may seem like just so much rhetoric, but the solid fact is that no

president, no governmental agency, no social program, and no new law is going

to lift us up. Only we can accomplish

that.

For

inspiration and solutions, we need look no further than the men and women of

honor in our past. There are many to

choose from. Our history is rich with

individuals whose character, sacrifices, and accomplishments were beyond

reproach. Our past offers blueprints for

success, unlike the unproven rhetoric of a contemporary pundit with a gift of

gab.

We

must embrace the mantle of responsibility in the same fashion as our forebears

once did. We must exchange ideas. We must talk and write and talk some

more.

And

we must complain. Our founders changed

the world before the days of mass communication. They did it by talking and writing, one at a

time, day after day, without letup. Can

we not do the same? Can we afford not

to?

We

should use this 150th Sesquicentennial as a springboard to infuse one another

with hope, the hope that dwells within each of us. The hope that makes us get up and go to work

each morning, the hope that makes us have children, the hope that inspires us

to think positively about possibilities, the hope that makes us believe in a

bright future.

--- Pub.

|

| Past Publisher's Forums click an issue number to view |

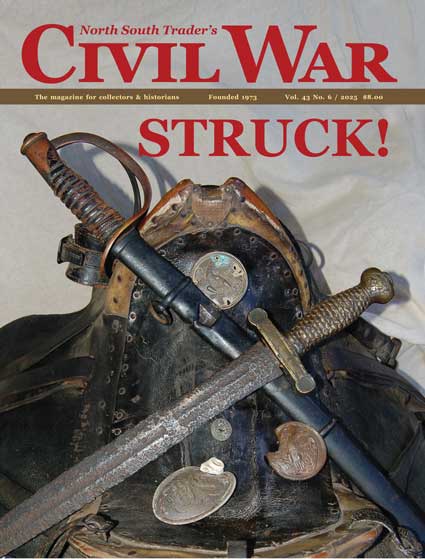

| 43-6 |

| 43-5 |

| 43-4 |

| 43-3 |

| 43-2 |

| 42-3 |

| 42-3 |

| 42-3 |

| 42-3 |

| 42-3 |

| 41-6 |

| 41-5 |

| 41-1 |

| 40-5 |

| 40-4 |

| 40-3 |

| 40-1 |

| 39-6 |

| 39-5 |

| 39-4 |

| 39-3 |

| 39-2 |

| 39-1 |

| 38-3 |

| 38-2 |

| 38-1 |

| 37-6 |

| 37-5 |

| 37-3 |

| 37-2 |

| 37-1 |

| 36-9 |

| 36-6 |

| 36-5 |

| 36-4 |

| 36-3 |

| 36-2 |

| 36-1 |

| 35-6 |

| 35-5 |

| 35-4 |

| 35-3 |

| 35-2 |

| 35-1 |