|

Publisher's Forum Issue: 35-3 |

|

I remember many years ago reading a collection of letters between a Union infantryman and his family. The soldier survived the conflict and returned home with the treasured letters that had kept his spirits buoyed through countless rereads on bleak and lonely days. His family had also kept the letters he had mailed home from distant camps and battlefields.

Interpolating from the dates and the references to previous letters, it was clear that the delivery times were generally quite swift. Packages referred to in several of the letters indicated that they, too, had been delivered far more speedily than I had assumed of mid-19th century mail service. I had thought that mail traveled very slowly and with a great deal of uncertainty during that era. I wondered if this soldier's experience was simply good fortune or if it was the norm.

As time went by I encountered other documents that confirmed my new belief that prompt and efficient mail service was not that uncommon 150 years ago. Missives from loved ones and packages containing foodstuffs generally arrived quickly enough to prevent spoilage.

I found this surprising in light of the available modes of transportation. In addition to these transportation limitations, there were also lack of regulation, literacy, and a host of other obstacles that could potentially interfere with mail delivery.

I discovered yet another surprise: Valuables and currency were commonly shipped with relative safety.

Of course, at times the service was spotty. Inclement weather, remote locations, Indian uprisings, and a host of other impediments of man and nature conspired to interfere with service, but it was clear that there was a dedication exhibited by those entrusted with the mail.

Jump forward to 2011, and we find that we have recently encountered a lagtime of six to nine weeks for delivery of a magazine and a week to ten days for a letter or a bill. Despite airplanes, highspeed trains, ships, and interstate trucking, most mail could arrive faster today if it traveled by hitchhiker.

More, just this week I received someone else's mail. It was my post office box number, all right; it was not my town, state, nor zip code.

Damage and theft in the mail are all too common these days as well. Despite 150 years of improvements and regulations, cutbacks, streamlining, layoffs, and increased rates, our once-reliable postal service is now operating at a snail's pace and losing billions of dollars annually.

I suspect that sometime in the future, when reason has emerged from hibernation and political correctness has gone the way of the Inquisition, honest analysis will reveal how this happened and why. Today we are left to wonder: Is it inefficient systems, too much mail, restrictive union regulations, substandard employee requirements? Someone probably knows, but they aren't telling.

For those lucky subscribers for whom this subject may seem a mystery, count yourselves fortunate. Our less fortunate subscribers have recently waited weeks for their magazines to arrive. We are working with the post office and our congressman's office to rectify the situation, but still the anwers come at a snail's pace—or slower. It seems that the dedication that was once the hallmark of the postal service (“Neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of night”) has been replaced by indifference or incompetence.

We hope for better in the future.

On another matter, most of you have heard by now of the censoring of Mark Twain's literary masterpiece Huckleberry Finn. In an utterly astonishingly display of arrogance, a previously unknown college professor of even less well-known accomplishments, bearing a name out of a Dickens novel, Allen Gribben, decided to correct Twain.

He determined that Twain's use of the word “nigger” and “Injun” in much of the book's dialogue was offensive to today's young readers whose eyes and ears had not encountered such language until reading Twain. The two words were replaced with “slave” and “Indian.” Also “corrected” was the expression “half breed,” which the sensitive Prof. Gribben sanitized to read “half blood.”

The editor of the new version explained that these “updatings” will be performed on both Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer.

Bear in mind that none other than Ernest Hemingway once said of Huckleberry Finn, “It's the best book we've had. All American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.”

Despite such lofty praise, Al Gribben believes Twain needs correcting and he is the man to do it.

The fact is that Twain's use of those words was very deliberately done to portray the casual use of the term in the context of Huck's environment, thus effectively illustrating the dehumanizing nature of slavery. Sanitizing the dialogue strips the tale of its power to illuminate and educate. “Injun” was a common term in the 19th and 20th centuries, and in Twain's work it well illustrates a linguistic idiom of the day. I'm quite sure Injun, Indian, redskin, red man, and savage were all equally mystifying and inconsequential expressions to those who decorated their homes with the dripping scalps of their victims during Twain's lifetime.

As far as “half breed” goes, I can only imagine that the professor decided to avoid the risk of polluting young minds with a less than polite term to describe people of mixed race. It was up to him, apparently, to alter history.

Predictably, there has been much debate about this new edition. Defenders have explained that Twain's books have always been controversial and are still often banned—usually at the behest of parents who never read or understood the contents and its rightful place in both literature and the truth of history.

The same defenders of the whitewashing say that removing the awful words will allow more youngsters to read Twain. I find such explanations utterly amazing. Reading Huck's adventures is itself an adventure in which the reader learns, along with Huck, about life and humanity.

I suppose the same people who grimace at Huck's language would support editing the Bible to remove all reference to God to make it a pleasant read for atheists.

Twain was, in fact, among the first great American writers to excoriate slavery. He was perhaps the first American writer to educate children on the basic equality of human beings in a medium that young people could easily appreciate and identify with.

We can but hope that this absurd “revision” will provide a great tool for enlightened educators to teach children the kind of lesson Twain would have relished: exposing the arrogance of misguided, pompous fools.

I'll add that there is precedent for such expurgation of potentially offensive passages in literature. In the 19th century, Thomas Bowdler published a “less offensive” version of Shakespeare. That was followed by a cleaned-up version of the racy Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Bowdler's prissy work has long been the sneered at, and it even gave rise to the term “bowdlerize,” spoken with ridicule.

And history has a way of repeating itself.

—Pub.

The publisher welcomes correspondence from readers. Write NSTCW, P.O. Box 631, Orange, VA 22960 or e-mail publisher@nstcivilwar.com

|

| Past Publisher's Forums click an issue number to view |

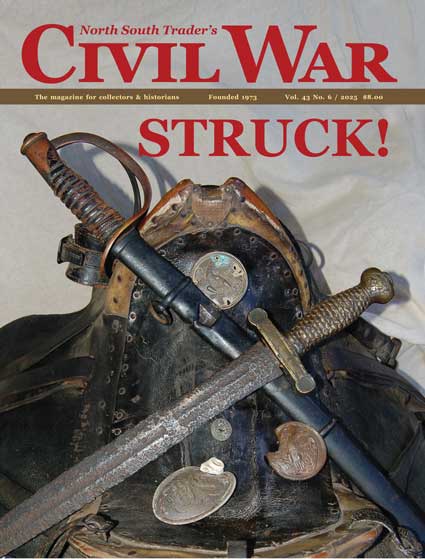

| 43-6 |

| 43-5 |

| 43-4 |

| 43-3 |

| 43-2 |

| 42-3 |

| 42-3 |

| 42-3 |

| 42-3 |

| 42-3 |

| 41-6 |

| 41-5 |

| 41-1 |

| 40-5 |

| 40-4 |

| 40-3 |

| 40-1 |

| 39-6 |

| 39-5 |

| 39-4 |

| 39-3 |

| 39-2 |

| 39-1 |

| 38-3 |

| 38-2 |

| 38-1 |

| 37-6 |

| 37-5 |

| 37-4 |

| 37-3 |

| 37-2 |

| 37-1 |

| 36-9 |

| 36-6 |

| 36-5 |

| 36-4 |

| 36-3 |

| 36-2 |

| 36-1 |

| 35-6 |

| 35-5 |

| 35-4 |

| 35-2 |

| 35-1 |